If there is one thing that is a constant about Brooklyn, it’s that New York’s most populated borough is ever-changing and multifarious in the new trends it generates, making it a perfect environment for experimentation. So, now that a massive 1 million-square-foot project in the form of a European village is slated to go up in one its most populated neighborhoods, Bushwick, the project reverberates in such a way that the rest of the country takes notice. To put the outsized impact of the project in perspective, if Brooklyn was its own city, it would follow Los Angeles and Chicago, by population. So we are talking about an issue to scale, and not merely something that is trendy because it’s coming from hipster central.

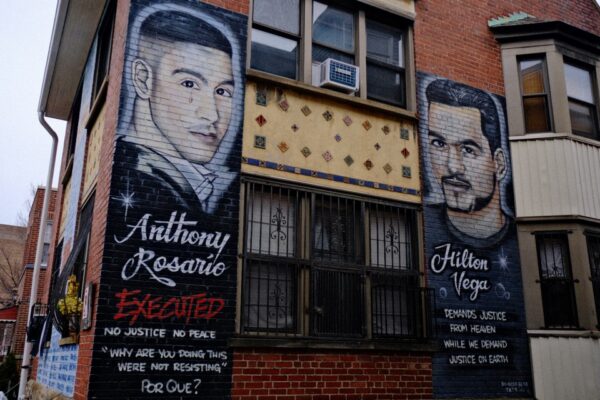

Developed by Brooklyn–based developer All Year Management, owned by Yoel Goldman, New York firm ODA‘s project, which is technically named 123 Melrose, has been suggestively dubbed Bushwick II by local media outlets. The two-block, multifaceted, mixed-use multifamily site will feature high-end amenties such as art galleries, coffee shops, lounges, gyms, and a rooftop farm with a “hop yard” to boot—the last of which harkens back to the site’s original use as a brewery. Comprised of 900 units, the developer has said that at least 20 percent will be used for affordable housing—although local residents are skeptical of this, and for maybe some good reasons. In the last decade, the mostly Hispanic community has seen gentrification bring skyrocketing prices for both single-family homes and apartment rentals.

ARCHITECT spoke to ODA’s principal Eran Chen, AIA, about the developmentand how he has addressed all of these issues while still maintaining the identity that is Bushwick.

Bushwick II is significant both for its location and that is the largest project ODA has taken on to date. What do you hope to achieve in realizing this project?

In this project, we are reinventing the typical [New York City] grid system by transforming it into something much more permeable, opening typically private courtyards to the public, as well as to building dwellers. It’s a bit like overlapping the [New York City] grid with an old European city—instead of organizing some buildings on an empty lot, we carve public and communal spaces out of a solid mass, creating a network of pedestrian streets and courtyards framed by commercial and amenity spaces. The result is a true departure from the systematic, dead-end, live-work boxes into a three-dimensional living experience. This project takes our notion of “unboxing buildings” and applies it on a city scale.

The project is massive. A million square feet. Considering the neighborhood is characterized mostly by apartment buildings and single-family houses, how will you holistically integrate a complex at this size into the area?

There is no question that this project, with its size and architectural language, will feel somewhat upscale relative to what is currently there. However, the design concept is not of two mega-buildings, but rather a cluster of buildings that form a neighborhood. The voids that we created between the buildings are, to an extent, more important than the buildings themselves. The newly erected neighborhood park, the pedestrian alleys and courtyards are what I believe people will see and feel. Not just the structure itself. Although areas of Bushwick today are disused and neglected, others have been organically fragmented in a way that allows for a human scale experience. We used this vernacular as a model for the new complex, so that the human qualities of Bushwick will not only be maintained, but strengthened.

Bushwick is also a working-class neighborhood. Does the design concept pay homage to that, or reflect it in any way?

I spent a lot of time contemplating how the new social fabric would connect with the existing, working-class neighborhood. There’s been great architectural effort to open the building up to its neighbors by sharing the exterior communal spaces with the general public. It is perhaps the most publicly accessible project I’ve ever designed and arguably the most publicly accessible private project ever constructed in [New York City]. Architecture done right has the power to connect people. I’m a big believer in that.

There is also a major concern of gentrification in this area. Are you attempting to ameliorate this issue in any way?

Absolutely. Gentrification as we have come to know it is a negative process by which upper income groups squeeze out the existing community. Although some of that will always be true as the zoning code changes and the city continues to grow, I strongly believe that with the right architectural formulas, and integrating local community access to the benefits that renewal brings, there’s greater chance for a win-win situation.

For example, we are reaching out to local business owners to bring their shops into our courtyards at a reduced rent, and we’re inviting local artists to participate in public art areas within the project. ODA is also working with a nonprofit organization to collaborate with the community on building playgrounds and other structures within the project for collective use.

What kind of design methods or materials have you chosen so that it complements the region?

We are using simple materials prevalent locally, like brick and steel, to articulate the facades with an emphasis on transparency at the street level in order to express openness and a sense of security.

An interesting aspect of Bushwick II is that it is features plazas, coffee shops, art galleries, study and recreational areas, and the like. What inspired this?

I am a big believer in mixed-use urban renewal and a big advocate for residential projects with light industrial programs and creative offices. Life in cities used to be like that. What we need to learn now is how to apply these uses while dealing with increasing density within the boundaries of [New York City]’s zoning regulations. This is a big part of what we do here at ODA—we’re constantly seeking new forms of architecture that will sustain all types of city life and restore our engagement with our immediate environment and with one another.

What do you hope the project will say to those who inhabit and live around it in the future?

As architects, rather than feel stifled by the ever-changing constraints of city life, we should feel inspired by them to find new solutions that will begin to restore all that we have lost. In the rich connections once played out daily on stoops and sidewalks, between neighbors and passersby, there was a vibrancy and interdependence. Not only between people, but amid the buildings within a given streetscape, a sense of community in which we all played our part.

Along the way, we surrendered to the vertical sprawl by sacrificing the very things that sustain us. We began building sealed glass towers, living in increasing isolation from each other and from the street and neighborhoods around us. From these sleek podiums, we grew progressively disconnected not only from the communities in which we live, but from the natural world receding beyond the sprawl.

Rheingold Brewery’s site presents an extraordinary opportunity to redefine some very fundamental aspects of what we’ve come to accept in urban living. While technically a building by [New York City Department of Buildings] standards, we have conceived it as a series of nooks and voids, social pockets within which communities can grow and thrive. By interrupting the rigid order of a typical NYC street grid and blending it with the sequencing of a European village, the path becomes a meandering courtyard rather than a direct line from point A to B, a place where one can wander and experience the moments of discovery and interaction that are currently in such short supply in our daily lives.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.